Canal

Tlalocan – The place of origin, an investigation into one of Teotihuacan’s main palaces

- 26/08/2025

- Posted by: Redacción

- Categoría: Essays

Coming to this investigation was somewhat of a coincidence, as most things are when you are being led by the sacred spirit. My relationship with Teotihuacan is almost as old as me, and the importance it has in my personal life, as well as in the Mesoamerican world, can go overlooked. For this reason, it was fair that I dedicated some time to looking into something within this ancestral city with my own investigative eyes, starting from my own understanding of 25 years of walking the red path of the Toltecs.

Toltec culture is spread across Mesoamerica, and places to learn and contact it are as abundant as there are places and towns in Mexico. There is no single temple, place, people, or teaching that you must go to if you are to receive the wisdom from this, one of the five oldest civilizations in the world. Anywhere you choose, or that chooses you, will have a different and unique teaching awaiting for you. Be it a mountain, a river, a monumental zone, or a human teacher awaiting in some unknown indigenous town, all have something unique to teach, and that teaching will be for you as central and pivotal as any can be.

However, we like belly buttons, centers, and it’s probably no coincidence that the part -xicco- in Mexico means place of the belly button, or central place. I dare to challenge everything, ponder about how one word and its translation can be given different meanings, beyond the accepted ones. The Nahuatl word given to the Mesoamerican continent—Anahuac—is translated as “land surrounded by water,” and is quite a proper way to call this section of the North American continent that we modernly call Mesoamerica, that includes parts of Mexico, Guatemala, and Belize. But strictly speaking, the word Anahuac can also be understood (from my direct understanding of the Nahuatl language) as close to the water, hugged by water, and that is not necessarily the whole of the landmass that is hugged by extensive seas, as Mexico is, but rather, a place that is found within an area with water, and that would be the region in the valley of Mexico where there was once a lake, and where the biggest sites of civilization flourished: Teotihuacan, to the north of the lake, 1,500 years ago, and Tenochtitlan, in the middle of the lake, some 600 years ago.

In a way, it can be felt, ancient cultures in this continent liked having central sites, central regions, places of origin, sources, points, belly buttons, and Teotihuacan should be considered, and is considered by the practitioners of Toltec culture, as the main central sacred place of the whole continent. As far as my journeying was taking me to so many other places of teaching, a calling was made to come here and touch base. All of the North and South American’s ancestral native culture and ways can agree on the coming together, the consideration that they belong to a mother culture, a mother root, as their worldviews all are interlaced, compatible, and mutually intelligible. The other agreement they share is that we are coming to the end of a long era and that humanity must be reborn, that it cannot continue as it is, and that one of the main sources for the knowledge, information, and inspiration on how to create this new humanity and new era, comes from them, from the race of earth, from the native peoples of this continent. This has been the calling that we have been following and resonating with, an axial part of Native Journey, the Circle of Medicine, the Muxuq Nina tribe, and the Union of the Hearts of the Eagle and the Condor.

This path of prophecy we’ve been following and leading wove in time a moment of calling and awakening. Followed and pushed forward by many that have heard the calling, we wanted to carry out our own ceremony in representation. It was the lighting of the New Fire that took place on the Venus-Earth conjunction of March 23, 2025, in a cave in Teotihuacan. The ingredients appeared and the few who could, heard the call and assisted. Around this event we organized the first Toltec Fire Initiation journey in Teotihuacan. Organizing this journey for the participating guests and initiates propelled me to a deeper journey of research about this place and the culture that built it. 25 years of previous research and experience was a solid basal structure to begin with, but now, I had to take it further and know a lot more. I invested in buying the books about it I hadn’t read and set out on a quest of my own of understanding beyond the sometimes biased views of different researchers—archaeologists mainly. It’s a quest that is really just starting, as I discover that with the years, enlightenment comes not from the books, but from living under the worldview this culture built. Things that appear to be a mystery for the academics, are not to me. Narratives that rely heavily on a certain monism and therefore may seem biased, can be better understood if we can shift our conceptual frame of understanding and seek a different way of living. This can only be achieved through a sincere approach and a consequential detachment and abandonment of a consumerist mindset. Those who live to study from the comfort of their capitalist armchair, not wanting desperately a transformation of that life and its implications, reflect a certain lack of congruence and a falsehood or shallowness in what they profess. The knowledge must be excavated so that it can help us build something like, and better than Teotihuacan. Rather, most of the time the knowledge and research falls into the hands of those who wish to pull us further away from this natural understanding, keeping us trapped in a system designed to take away our freedom and a plentiful life for us and the coming generations.

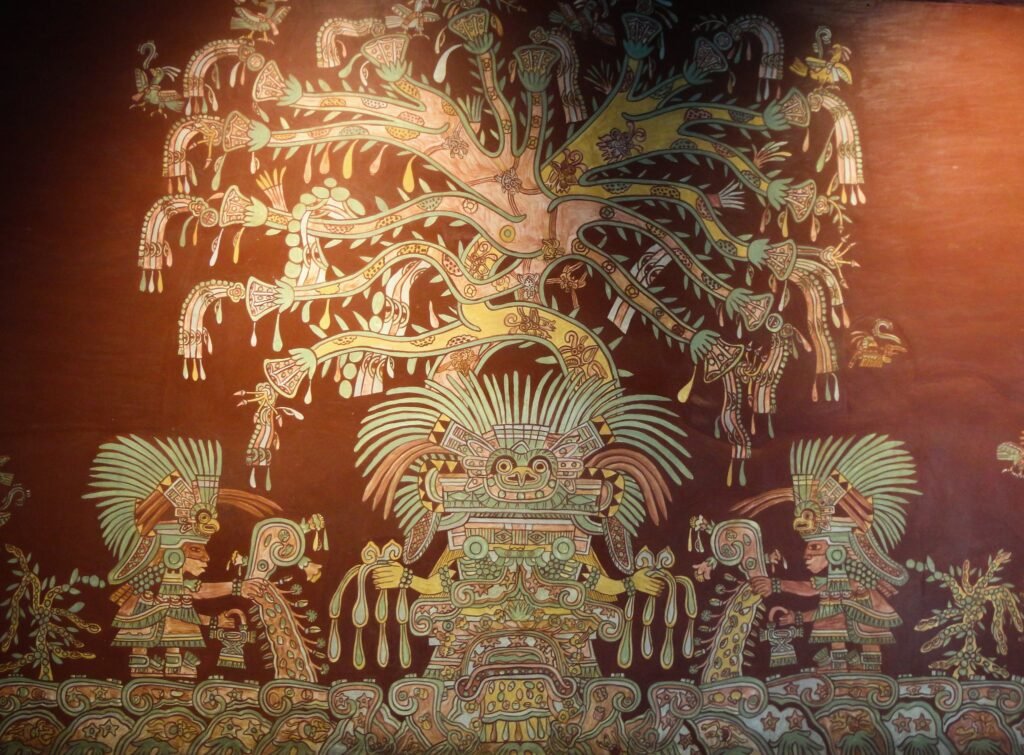

This text will touch on everything, as something coming from the Toltec worldview must. No fragmentation. There can be diversity, difference, specialty, and we will specialize on the description and understanding of the Tlalocan mural of the Tepantitla palace in Teotihuacan; but this specialization must not divorce us and draw us away from everything else that must be stated and comprehended. I won’t describe the Pyramids nor even the unique and peerless architectural scheme of the monumental zone. Everything will be centered around this mural found in one of the palaces near, but outside what today is the monumental zone: Tepantitla. The short explanation is given here, in this video which was also a cornerstone for this text and research. If you care for it, give it a watch and if you wish to deepen into the understanding, then you may continue reading this investigation.

The texts found in Fray Bernardino de Sahagún’s relation (which by the way was written by native informants, not really by any Spaniard) speak about the Tlalocan as an earthly paradise that is always green, lush and filled with food and flowers, where those who die unfortunate deaths and deaths related to water go to, such as dying from a lightning strike, from drowning, from incurable and contagious diseases, and as I mention in the video, children that didn’t get to develop fully in this life. This last part comes from another paradise actually called the Chichihualcuauhco, which means the place of the tree of breasts. It is said in the texts that children who would die too early on, and that didn’t get to eat corn yet, would go to it, a place of origin. Additionally, in another part of the book, where it mentions the celebrations to the descending waters—Atlcahualo—in the civil calendar, it mentions that children sacrificed to Tláloc, the god of rain (translated literally as the earth’s nectar) would become tlaloques, companions of Tláloc, and it was up to them to make the rain happen. Other parts of the book where the prayers to Tláloc are described, which would occur during droughts, make the point and the importance of the tlaloques as mediators for Tláloc, and that reside in the different places of the earth, probably where the children were sacrificed. These texts, bear in mind, are a relation that speaks about the worldviews, practices, and religion of the Aztecs, or Mexica, who flourished in the region from 1321 to 1521 A.D. To everyone’s astonishment, these written relations have an amazing resemblance with the Tlalocan mural, painted around 450 A.D., at a time when the Aztecs hadn’t appeared on the map. It is clear with this and with other evidence that the modern Mexica or Aztecs had inherited the worldview of the ancient Teotihuacans which, by the way, we don’t even know how to name properly, as we don’t know exactly what language they spoke and hence what they called themselves. For us the practitioners, the whole of the continent and cultures that inhabited it, stretching as far back in time as you can, are called Toltecs.

We can make a differentiation though, where maybe some cultures weren’t exactly “Toltecs”, and deepen into controversial reconstructions of the Mesoamerican past. With this we will touch on sensitive topics like the fact that there were “kingdoms”, “civilizations”, “wars”, and “sacrifices”, things that we practice more than ever today, but without a spiritual, honorable, or sacred context to it (and probably why we are blind about it and criticize and demean the civilizations that did, calling them savages). What geographically is considered Mesoamerica, can be summarized as a land vast with mountains, valleys, and a reliable source of rainfall (though this varies greatly depending on the specific place). This allowed for settled civilizations that relied on agriculture and, with the surplus that this brings, constructed large settlements, irrigation structures, temples, observatories, libraries, roads, you name it. As we travel north from central Mexico, we step out of this “Mesoamerica” and begin entering what is called “Aridoamerica”, where hunting and gathering was a more reliable way of living. The land shaped the people, and the people that inhabited Aridoamerica had significantly different ways of living and thinking. Reconstructing a broad continental history we can inquire on what we know about the Iroquois Confederacy and how that got started, where a woman once “got tired” of the “mound builders” and walked away from that, walking away too from what we are sensitive about: large civilizations, wars, and human sacrifices. Other sources mention a negative view towards human sacrifices, the Evangelion of Quetzalcoatl, for example, a compilation of “Huehuetlahtoltin” or Nahuatl oral traditions, mentions that the avatar Se Acatl Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl that arrived around 1000 A.D. and became very briefly king of the Toltecs in Tula, despised and banned human sacrifices during his rule, before he was cast out by Tezcatlipoca priests.

Not wanting to untangle the sensitivity about this specific topic and give some kind of explanation as to how these two (or more) different points of view came about, something I will share later when I compare (and study further) Tezcatlipoca and Quetzalcoatl worship legacies, I do want to say that we can distill all this diversity and difference and speak about two main ways of “being” that existed throughout North America, where both ways got intertwined, combined, and coexisted and where not each peculiar way was “the right way,” they were simply different and complementary. One would be the “Chichimec” way, where people lived without “building mounds” and in a more intimate relationship with nature, relying mostly on harvesting and hunting, or as I like to think of it now: “large herd and large land keeping”; and the other the Toltec way, where transforming the land, building large structures, and developing extensive populations and complex spiritual and scientific constructs, was accepted and welcome, sometimes in detriment of Chichimec sensitivities.

These two ways of being coexisted and clashed, at times, throughout North American history. Let’s imagine a tribe of Toltec people, immigrating from their large settlement because of a volcanic eruption that destroyed their city (this happened more than once), and entering what would seem bare, empty land, void of towns, people, and civilization, but that actually did have owners, keepers, who were the “nomads”. The borders between these two lands, these two worldviews, did not quite exist, they meshed. The nomads then, wouldn’t be happy about it, for many natural, intuitive reasons. Being under the rule of natural law, they would resort to killing or attacking the immigrating or recently settling Toltecs, because they were stealing or hurting what they thought was their land. Conflict was not out of greed, but because of the nature of the natural world, of which humans are part of. There are many pieces of evidence that speak of a show of mutual respect, of mutual interwovenness, of the integration of the wisdom created from living in both ways.

Conflict and the dynamic of territorial stewardship became part of the natural and sacred balance, portrayed in temples and in the rites themselves, the worldview, like the Flowered Wars, the warrior schools, and the paradise of the sun, where the Mexica warriors would go to. It’s safe to assume, that the Mexica brought a new era, a new stage and according to some, a worse version of the old, but it was the old nonetheless, the same culture, the same land, the same interwoven ways that sought renewal. In that quest, the Tezcatlipoca, smoking mirror nature of the universe, the amorality of the cosmos and experimental spirit of existentiality, maybe, could be argued, brought a final doom to all. If at the time of the Mexica, there wouldn’t have been dislikes and conflicts between the nations (The Totonacs, where Cortés first arrived, the Tlaxcaltecs, the people that lived between them and the Mexica, and the Tarascans, the extensive empire that spanned beyond, all had strong animosity against the Mexica), maybe Cortés wouldn’t have been successful, and the empire of true greed, disease, and deceit wouldn’t have taken over these lands. We had somehow spiritually failed, and that led to our final demise.

Winding back time to the Toltecs of Teotihuacan, a lot fewer information can be gathered about what was going on back then. I will allow myself to rely heavily on informed vision and imagination. Around a wild land where the ocean-moist mountain forests transitioned to the arid high plateau deserts of the central mexican inland, a lake surrounded by volcanoes was an energetic site no one could refuse. It was geographically at the center of it all, and for an agricultural people, the dry but fertile flatlands could become a lush paradise thanks to a lovely mountain with a spring that came out of it, next to the mines of the most precious tool-making material at the time, obsidian. With a little help, with the wisdom of those who knew, of probably those who inherited the knowledge and legacy of prediluvian cultures from abroad, that mountain spring would be used to transform the land in front of it into a real paradise on earth, and that’s what is (also) depicted on the mural of the Tlalocan.

North American native worldview is not good with lines and borders, sections and dissections. The border between an other-dimension paradise on earth the undeserved dead would go to and a paradise on earth that actually physically existed, let’s try and not see that line, as they did. In the mural, the similarity of the mountain at the center, where water springs out like a feather serpent and weaves around to make the frame for the whole mural in a decorative but depictive manner, is notable. A sky band lies above the land where the mountain is and the kids are playing amongst butterflies. Above the sky, at the center, is the great Tláloc with an impressive headdress that also represents the deities of Teotihuacan, the great owl (which could have been a famous Mayan ruler that governed in Teotihuacan). Eagle, owl or parrot is not clear to me, I could be mistaken, but it reminds me of this figure, all so present in so many other murals and palaces. Standing on the sky band are what I now call the Teachers, the humans with crocodile headdresses. They are abundantly depicted throughout the palace, especially in the room that is behind the one with the Tlalocan mural. From their hands fall shells, seeds, water, signs of life and abundance. They are singing and speaking, and their words are wisdom. They are the fathers of civilization, the creators of the abundance, of life. Without them, this would be an arid valley with a few rabbits jumping around. With them, a 250,000 inhabitant city with all their animals and crops thrived.

We make distinctions and borders, between teachers, wise men, gods and demigods, but those borders are not in that mural. That palace was the school, the place where the great legacies were transmitted from one heir to the next. It was the source of wisdom, where the mystical tree of life stood, depicted above the great Tláloc. This tree reminds me of the Chichihualcuauhco, the tree of breasts, I draw no borders. Humans are to this cosmos and earth, the great smoking mirror. The appendix of modern culture and civilization (if you can call that to our times) says we are the very last product of a long line of creation and evolution. But apply the mirror of a worldview that is proved (through latest quantum discoveries) to be more solid where time is not lineal, and then human, the great human, the Tekuhtli, the lords with those great headdresses, are the creators too of life; the planet and the cosmos, they, we, are the source. This great tree of life is there depicted, in that temple, and the temple was abandoned and destroyed. Like it and likely with it, our access to this paradise and this source has been halted. As we no longer bear this knowledge and perceive the cosmos we live in with this unity, without the borders, we are effectively cast out of the earthly paradise.

Will be continued…

“This has been the calling that we have been following and resonating with, an axial part of Native Journey, the Circle of Medicine, the Muxuq Nina tribe, and the Union of the Hearts of the Eagle and the Condor.”

This is also the calling – and the path – that resonates with me (I am on another continent). Thank you for rich information and the comprehensive message and presentation). I will follow this series of texts. Very interesting about the Toltecs, Aztecs and Mexica. I’m learning from afar. One day I will visit Mesoamerica again.

Muchas gracias for the offering, sharing.

JJM

Thank you for such a wonderful comment Jim! It’s really helpful to get the inspiration to keep writing and researching. Be very welcome when you are able to come!